November, 2016

The Swedish artist Jonas Lund combines media art deconstruction strategies with contemporary art practices. This results in works that are often participatory, conceptual, or performance-based. In his work Lund easily moves between online and offline systems, and between technological and socio-cultural constructs, all the while working the analogies that bind them. He first got international recognition in 2013 with his first solo exhibition the Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), at the Rotterdam art initiative MAMA. For this show Lund created an elaborate analytical software system that told him how to construct each piece in the exhibition, with title and all, based on work by the top-selling artists of the time.

Jonas Lund - Selfportrait

Jonas Lund - Selfportrait

Software and network are basic properties of Jonas Lund’s praxis, both materially and conceptually. Some examples: in 2011 Lund made Blue Crush, a typical net art work in which blue pop up windows take over and crash the browser, and In Search of Lost Time, a Twitter version of the book by Proust, in which the book is broken down in 140 character sections tweeted over the course of 6,5 years. In 2012 he made The Paintshop.biz, a combination of interactive website, paintshop and website, in which people could design, print and sell their own paintings. The same year Lund also wrote an algorithm for a performance on Facebook called 1,164,041 Or How I Failed In Getting The Guinness World Book Of Record Of Most Comments On A Facebook Post. In the pivotal year 2013 Lund went from creating works like Paint Your Own Pizza (for Eyebeam), a work that was very similar to The Paintshop.biz, to almost completely dedicating himself to handling the art world as a system after his graduation. Lund commented on the art market already in 2011 with the spam inspired work Collection Enlargement and with several other works since. With his first solo show Jonas Lund however moved from the commentator position to that of the hacker, engineer, or systems architect.

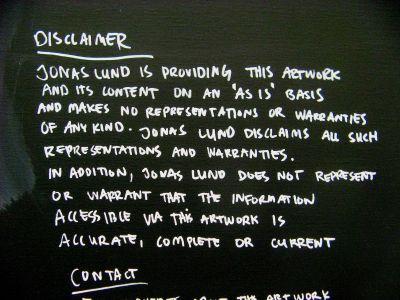

Lund takes an active role in the positioning and distribution of his work, far beyond the confines of the studio or the gallery. While his art still works as commentary or criticism, installation works like Flip City (2014) or analytical works like Projected Outcomes (2014) are also tools to develop future interventions, if necessary. In Flip City paintings are fitted with GPS trackers to follow them on their journeys after sales. In Projected Outcomes Lund made a daily re-assessment of the costs of the exhibition The Value of Nothing on a blackboard in that show. Lund invents at times absurd or ironic methodical solutions to deal with an often equally absurd and unintelligible art world. I interview Lund in email, while he travels from Brazil to LA to Berlin.

(Email interview, April 2015, published in German in Kunstforum November 2016)

JB: On therealjonas.com you tell the story of how your main website was hijacked by domain snatchers in 2012. In this story there is a gap of nine years between your first steps online in 2003 to when the hijack occurred. In this time you moved from being a young photographer to working as an artist creating various forms of code art. When did you start programming, and how did the transition from photographer to programmer go?

Lund: I started programming during the last years of my studies at the Rietveld. It started with me programming websites for friends and galleries and then grew. It became my main source of income for the next years. After graduating in photography I was quite fatigued by the medium. The act of taking an object or a subject and pointing a camera towards it and pressing the shutter felt impossible, so I took a very long break from it. During this time I discovered the whole world of net art. Once I started making online works, it was like a fresh breeze on a spring day, no obligations, not much hierarchy, not that many references to the past (mostly because most net art is so poorly documented), so you feel totally free. You can do it from your bed, couch or beach, and once you are done, you do not need anyone to tell you it is good and hang it on a gallery wall and have an opening and all that, you just publish it and then everyone can see. It is by the far the freest way of producing works of art.

Beyond that I have always had a huge fascination for systems, and particularly networked ones, to figure out how things work and how everything is connected, and online art is very much in the center of that.

JB: To me your work is net art and post-digital at the same time, in the sense that it transcends common interpretations of the Net and the digital as screen-based media. How do you see this yourself? I know most artists feel uncomfortable with any 'media label', or they at least adapt labels to the various contexts their work is presented in.

Lund: I used to care quite a lot about these labels and be strategic about it. I for instance would ask myself: should I participate in this year’s Transmediale, will the art world think less of me if I do, because it is so tech art. Once you're labeled with that you can forget about having cool shows at hip galleries, and you'll never be included in the Venice Biennale or have your work at Art Basel and whatever. I am at the point where I don't care anymore. Labellers are gonna label, haters gonna hate. As long as the work is good, the work is good, no matter the label or the scene. And by the way, most of the people at Transmediale are about 1500% nicer than the ones at Miami Art Basel.

Screenshot from Fair Warning, online commission at philips.com, 2016

JB: Digital media do not so much represent an entirely new sphere, and certainly not one in the realm of visual culture alone. They rather exist within and between earlier systems, which they amplify, twist, connect, break down, reinterpret, undermine, or sometimes replace entirely. Alexander Galloway even says the computer remediates the very conditions of being itself. How do you see this?

Lund: I think by now most of the things that influence our daily life are governed by digital systems: it is not so much as what is digital, as all is digital, to the point where talking about digital is in itself pointless. Post-digital, sounds a bit on the same level as post-internet, a kind of pretension that the Internet is ubiquitous, when less than half of the world is connected? Naturally the borders blur, and perhaps more people are getting an understanding of how digital systems are governing their lives, but I think we are nowhere near a level where I would use the label post-digital, on the contrary, we’re more likely pre-digital – a situation where the largest majority of the population has a very limited understanding of how these opaque systems of control are optimising our surroundings, me included. I mean, I talk about PageRank and EdgeRank as if I understand how they work, but I have a very limited understanding of them. I think even its creators have a pretty vague idea of the selection criteria they generate.

In my practice, I was never interested in the digital on its own, but only in its effects and consequences; works that only dealt with digital technologies for the sake of technology were endlessly tedious to me. It is not what brand of acrylic paint you use that is interesting right? I suppose I am not post-digital as I was never digital to begin with.

JB: In your work I see a few themes re-appearing again and again, respectively audience participation, pop culture, algorithmic play, and the art hack. Since you mention you were influenced by net art I wondered which artists specifically, because there are such different approaches. I can imagine artists from outside this field have inspired you as well. What works or artists have influenced you most and what attracted you about their work?

Lund: My idea of what is good and bad changes quite often, which I think is a blessing. Sometimes I see a piece that I used to hate and all of a sudden I love it. So talking about references, it depends on the day. I love JODI’s work, they pretty much covered everything there is to talk about online in one way or another. It is quite absurd how much work they have produced over the years and how difficult it can be to find it. In the beginning when I had no clue about net art it was great to run into Constant Dullaart’s Google pieces and all of Harm van den Dorpel’s old pieces and JODI’s work. They establish a lot of defaults: the domain as a title and the self-contained piece, the ‘hack’ of existing structures, the subversion of attention, the constant references to the now. It is work that operates within some type of system but at the same time exploits or embraces it, sometimes by punch lines, sometimes by more extensive dialogue, such as the works by Hans Haacke or Cory Arcangel do as well.

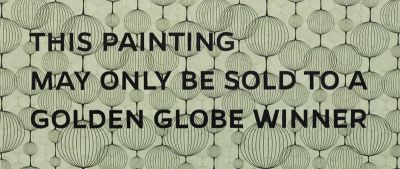

Detail from painting in Strings Attached, Steve Turner Gallery, LA, 2015

JB: Your work easily reminds of that of Hans Haacke, mostly because of his early systems art. Haacke’s work clearly includes a critical view of art’s wider economical context, from museum sponsors to investment bankers. It made certain art institutions shy away from his work. You are less outspoken, but I can imagine that in the current high-strung art market your work also touches a nerve. Have you received any praise or commentary from art professionals who say your work is good, but too problematic to show or buy, like Haacke has?

Lund: I suppose the way it is today is that all is good or there is no dialogue or commentary. The only way to find out about your critics is to listen carefully when people talk behind your back, as they will rarely, if ever, tell you in person. So to answer the question, so far nobody has mentioned that the work is too problematic to show, most likely because they did not bother telling me. The Strings Attached show generated some sour faces, but nothing too bad.

In terms of dependency, to be able to maintain a criticality towards the art world and the institutions Haacke took on a teaching job as part of his practice, to secure a stable income away from the whims of the market and the institutions, as a way to be independent. If you are not relying on the institutions and the market to pay your bills, I think it is much easier to adopt an ‘I don’t give fuck’ attitude. But is the critique valid if you are not really part of that market?

JB: What also comes to mind in relation to your work is Cornelia Sollfrank’s Net.Art Generator, cyberfeminist art from 1997. This work was created to subvert the first net art competition, organized by a Hamburg museum and for undermining the alleged male genius in nineties net.art. In The Fear of Missing Out you apply a similar strategy, but from the position of the underdog who wants to get on top. Your attitude seems to represent the changed situation of art online. There is a flood of new art blogs, art related social media activity and artist websites, compared to the mid nineties, and their influence reaches far beyond the Net. I wonder if this adds to the pressure to succeed, or to a feeling of humbleness. An artist today can hardly retreat from the art world into his studio anymore. How do you see this?

Lund: Being an artist was always a public thing, and the ‘public’ decides whether you’ve succeeded or not. Instagram adds yet another layer to all your FOMO [Fear of Missing Out, JB], inadequacies, and points of reference for what is good and bad. If a work gets 100+ likes it must be good right? The publicness adds both humbleness and stress at the same time, but most of all it speeds things up, and there is little time for reflection. The shelf life or half life [gaming term, JB] of the work becomes shorter, so to counter an increasing lack of attention you have to maintain consistency with new, better and bigger. It is an endless game you cannot win; yet everyone plays it.

When I am in Brazil all of that seems to matter less, because it is sunny and there is a pool. Then who cares if people like my Instagrams, because real life is good? But when I am in grey cold Europe, it matters a lot, as the attention conveys a promise of better options, a future that is brighter, with more friends, more fame, more success, more money and more glamour, so eventually you can end up by the pool in Brazil and enjoy the good life. Weird right?

Cheerfully Hats Sander Selfish, Coconut soap 7 min 50 sec video loop, 2013

JB: What seems missing from interviews you have given so far is any indication that you see your work moving beyond the purely technological. There is some mild irony here and there, but you generally stick to a description of your works as simple applications rather than as works for criticism or reflection. You speak about getting access to the art world as a system, or deciphering the logic behind it, but express no opinion about either. Why do you stick to this reserved attitude? Why was there no critical follow up after The Fear of Missing Out on the average shape of art objects today, for example?

Lund: I am often accused of being both cynical and ambiguous at the same time, which is interesting, but the alleged ambiguity comes from my point of view that artists should not preach their opinions. They should rather point towards certain structures and behaviours and then it is up to the viewer/audience to figure out what is going on and take a position towards it. Hans Ulrich Obrist famously said that the best way to move forward in your career is to never offend anyone by having too strong opinions, but rather just ask good questions.

JB: It surprised me to see a presentation at the Stedelijk Museum by your Amsterdam gallerist Marnix van Boetzelaer, who described your work Flip City simply as a set of paintings fitted with GPS trackers in order to follow them on their journey on the market. This seemed such a bland description of a potentially critical, postconceptual and intricate network piece that I wondered if the lack of critical depth around it is an act or really a problem. It seems to me you should speak out more and leave Hans Ulrich Obrist's opinion for what it is.

Lund: Most of my work has different entry levels and different ways to describe them. You can describe the surface level and you will get a ‘mhm’ or a good laugh or two from the audience, and then you can leave it at, or you can dig deeper and try and pick apart what is going on. Perhaps Marnix delivered the entry-level surface description, which means, that what he described was probably true, and someone probably laughed, but it left you wanting more.

I look at Flip City as a networked piece that at the same time attempts to demystify the art market system and embrace it. The work operates through the act of it being sold and resold; there are many levels of critique and some opportunism going on. It has also, which confuses some of the people from the more media oriented world, aesthetically pleasing paintings. It all comes from a point where I am trying to understand the art world system, as it is infinitely confusing to me. Most people have very little notion of what is going on, and what is good and bad and why, and why should you buy this piece or that. They ask themselves whether there is really something there or is it just the emperor’s new clothes on endless repeat?

JB: In the interviews with Gerben Willers in Dutch art magazine Metropolis M and with Annet Dekker at Furtherfield.org you stick to describing technical aspects of your work, and not much more. Your tendency to keep your position vague creates the strong opponents as well as the admirers of your work. To me it often seems as if your admirers are very willing to give you the benefit of the doubt, since you yourself stick so much to the surface of the actions and works you design. Your work’s appeal might develop through people interpreting these technical descriptions of your work in a critical way. Surely something more can be said about your work than "The underlying motivation for the work is treating art worlds as network based systems"? (From the interview with Annet Dekker)

Lund: Wait what, I have opponents of my work? They never told me, which is really sad, as it would be great to talk to a non-believer and see what their problem with the work is. Ok, so the work does the thing of describing what has happened in annoying detail, but it doesn't attempt to describe the affects and effects of the actions, because it is not up to me to decide what those are. It is up to whoever engages with the piece and they can interpret it any way they feel like. I think my position towards the art world and the art market is pretty clear at this point. I am using code and big data and other tactics to at the same time figure if there is a formula to determine what is good and bad (or if this is just completely subjective) and develop tactics and strategies for outsmarting that system, as I do not trust it at all and maintain a high degree of suspicion towards everything that is 'art'.

Gallery Analytics, 2013

JB: The value of art, specifically contemporary art, which seems to be one of your favorite topics, depends entirely on systems of trust. It depends on reputations of artists, collectors, curators, galleries, institutions etc. Trust, at times in the shape of blind faith, is a fundamental element of the investment practices that exist within the contemporary art market. There seems to be an unpredictable drive underlying the art market similar to the practices of the financial world, where there is only a reckless play with money that disregards all political realities, according to journalist Joris Luyendijk writing about London’s City in the Guardian. Surely you must be aware of this, and your systemic approach therefore could be more of an expression of fear or anger (rooted in suspicion). Your works intervene in the art world’s systems of trust, but instead of getting a grip on them, you probably at most create a shift in faith, in influence, and in power. Would that be enough for you? Where would you ideally take you work, what should it ultimately be part of?

Lund: To me the systematic approach is not based in fear or anger, but rather in confusion and failing to understand how things operate. It is something I stress quite often, and perhaps you can parallel that to fear, but it is the feeling of not knowing how you can tell one work apart from another when there is no agreement on what is art and what is not. My systematic approach is an attempt to come to grips with what is art, what is good and relevant art, is it something entirely subjective, and that is enough and good and fine, or is there something more essential?

Ultimately, I think it comes down to this: if there is no general accepted way of telling what is good and what is not, how can I know what I am doing is good enough? Is it solely based on my own subjective view in a completely ego/megalomaniac view of ‘my voice is more important’ or does the work only become good once it is approved by a third party – but then, who is this third party?

Artists work in a weird system of appraisal and self-doubt, since the institution of the art world determines what is a good relevant work of art. The third party that validates your work and your practice is constantly an unknown collection of art world players and that is something everyone has to deal with. My way of dealing with it is to try and game this unknown third party and say: wait a minute; this system that we are all part of is really weird right? It’s not an attempt to try and improve or even fix the problems, but rather a way of dealing with my own skepticism.